As the institution responsible for the preserving the official records of the United States, the National Archives holds around 10 billion records in the form of photographs, letters, government documents, maps, and more. The physical records are housed either in the main Archives building in Washington, D.C., or in one of several annexes elsewhere in the U.S. A cursory glance at the Archives.gov website makes it clear that only a fraction of these records have been converted into a digital format to be exhibited online. The Archives.gov website as a whole is rather cluttered with countless links, but the “featured online exhibits” page is a fairly simple list of short descriptions of and links to individual exhibits. Each exhibition is a separate entity, organized topically rather than chronologically, but they share a theme of using documents of the period as lenses through which to see historical events, or political or social change. The scope of the topics ranges from extremely broad (i.e. “Discovering the Civil War) to extremely specific (i.e. “When Nixon Met Elvis”). The one online exhibit drastically different from the others is the Digital Vaults, which is a separate flash based website offering a sample of 1200 records interlinked by tags and pathways (http://www.digitalvaults.org/).

Example 1: “The Deadly Virus: Influenza Epidemic of 1918” (http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/influenza-epidemic/)

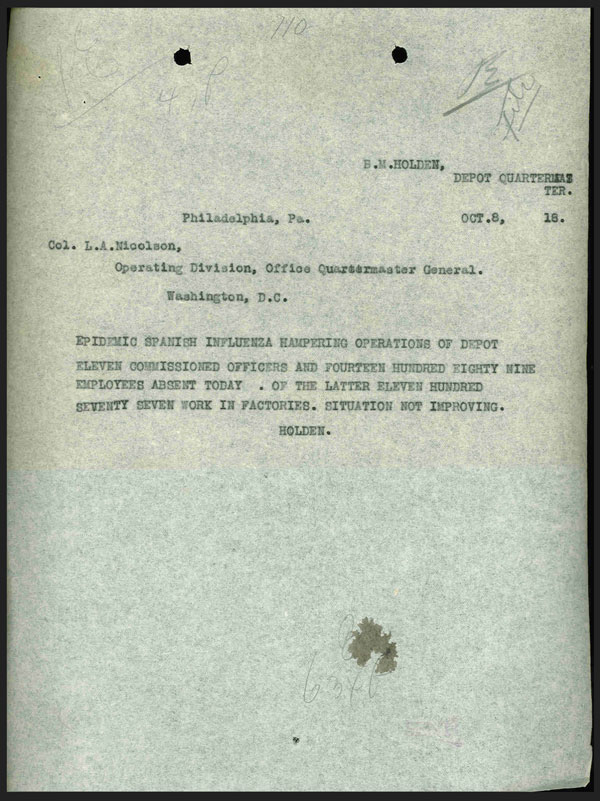

From the description that serves as the entry point into this exhibit, the mission is clearly to inform people about a disaster which claimed millions of lives but gets ignored as a major event in American history possibly due to its proximity to World War I. An individual curator is not listed, and there is no information on whether this exhibit ever had a physical presence, which suggests to me that it is a strictly online presentation of a selection of photographs, letters, telegrams, and copies of government directives. Each piece is presented alongside a text description explaining what it is pictured or written along with information about the origin of the document that puts it into context. Depending on the document, this information might include senders and recipients of telegrams or letters, the date a missive was sent or a photograph was taken, the location of photographs, or the government departments that drafted rules or regulations. An integral piece of information accompanying each record here is the location at which the physical record is held and either the individual record number or record group. These specifics along with the “How to Order Copies of These Records” suggests that the National Archives want to facilitate further research into the topic for a potential audience of students, teachers, or historians. As for the material properties of the documents, the flatness of the documents allows for easiness in being exhibited digitally. Although each scanned image or PDF is not presented at a very high resolution, one can still see physical characteristics like smudges or stamps on paper, hole punches, and the unevenness of a typewritten line in Figure 1, a military report from October 8, 1918. Even without being able to touch and feel the documents, they look fragile. Such is the nature of paper as it ages, so the lesson we can take away is that digital preservation is essential to extending the life of historical records as well as making them remotely accessible.

Example 2: The Digital Vaults (http://www.digitalvaults.org/)

In stark contrast to the influenza exhibit, the Digital Vaults is a far more complex arrangement of selected records from the Archives. While education and research are also goals here, so is optimizing interactivity. The aesthetic is smooth and modern rather than vintage and the organization is web-like rather than linear. Several options are available for entry points: selecting a random record, searching by keyword, or browsing the tags. The records are connected to each other by these tags and the relationships are shown visually. Each individual record is presented as a snapshot with a brief description, which can be zoomed in on and can be temporarily “collected” to be found again more easily. The restraints of materiality here are loosened as the records become part of a database of sorts where different combinations can be called up. For example, Thomas Edison’s patent for the incandescent light bulb can belong to three tag groups (patents, Thomas Edison, and famous people) instead of one physical location, although that is also listed. Instead of simply noting the record number, each item here links to its listing in the web-based Archival Research Catalog which has extremely detailed information on the item. Facilitating further research again seems to be a priority along with encouraging creativity by allowing the records to be used to make a mini-movie or poster.

In relation to the readings, some issues with these exhibitions are apparent. Similar to the documents from the Salem Witch Trials that Lisa Gitelman mentions, the documents in the National Archives “contain legible information, but they also contain plenty of other data by virtue of their materiality – their material existence or forensic properties” which include “the look, feel, and smell of the paper” (Gitelman 20). However, the tradeoff of accessibility and being able to digitally maneuver the objects to look at them in relationship to one another has enough value that it overshadows this material disconnect. A limitation of print archives that also applies to the digital ones is that “so-called hidden collections denote materials that are not documented and cataloged in a finding aid, and are thus invisible to the user” (Kirschenbaum 100). The majority of The National Archives’ collection is not available to users online, and it is mind-boggling to think of the server space that would be required to make 10 billion records accessible that way. The Archives are certainly keen on sharing whatever they can, as should be the goal of any institution with as vast of a collection of public records.

Sources:

Gitelman, Lisa. “Introduction: Writing Things Down, Storing Them Up” Scripts, Grooves, and Writing Machines: Representing Technology in the Edison Era (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999): 1-20.

Matthew G. Kirschenbaum. “Extreme Inscription: A Grammatology of the Hard Drive” In Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008): 1-23, 73-109.